August 05, 2025 by Marius Vach

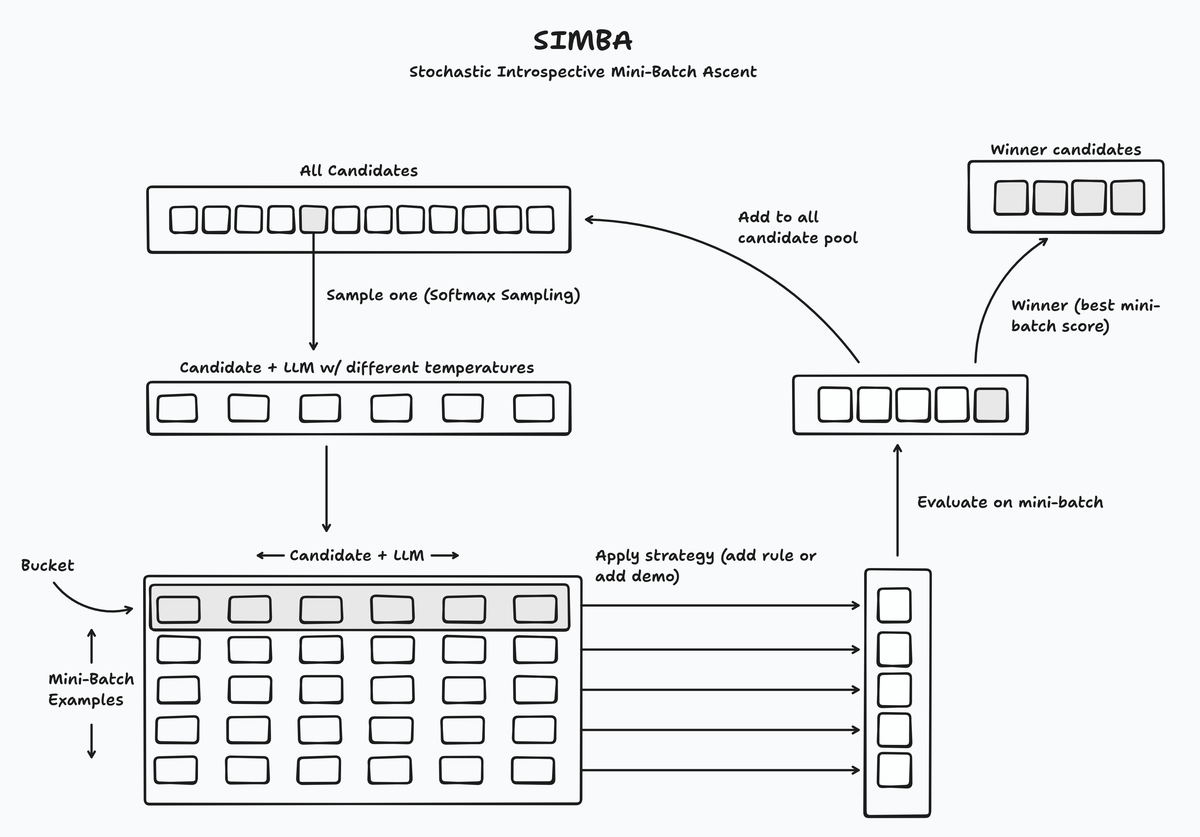

So let's dive in and see how this thing actually works.  Let’s go through the algorithm step by step: 1. SIMBA samples a subset (mini-batch) from your training data 2. It samples a candidate from the global candidate pool (in the beginning only your initial DSPy module). A candidate means the combination of instructions and demos. The sampling is done using softmax sampling which means that better performing candidates are more likely to be picked 1. 3. Then it combines the picked candidate with the LLM, but it creates different versions of the LLM, all with different temperatures - probably to avoid caching and to get diverse outputs. 4. It samples traces for every candidate + LLM combination and every example in your mini-batch (Quick reminder: a "trace" is the record of all intermediate inputs and outputs your DSPy program generates - basically the full reasoning path from input to final output. I covered this in detail in my [previous DSPy optimizers post](/posts/dspy-optimizers)). 5. SIMBA then groups traces from the same example together in buckets and sorts these buckets based on how variable the output of your model is on them (measured with your evaluation criterion). For this, SIMBA calculates different statistics of your evaluation metric for each bucket, like “difference between highest and lowest evaluation metric” or “difference between mean evaluation metric and highest evaluation metric”. The idea is that the examples where the output of your module varies a lot are likely particularly hard or edge cases. 6. Then we come to the heart of the algorithm. SIMBA then chooses one of two strategies for improving the candidate: - `append_a_rule`: SIMBA prompts the LLM to self-reflect on the output of the module and derive a rule that helps it to solve this particular task (example) better in the future. This is implemented as a DSPy module itself and reading the instructions of this DSPy module is quite instructive: > You will be given two trajectories of an LLM-driven program's execution. Your goal is to help the program's modules build up experience on how to maximize the reward value assigned to the program's outputs if it were to receive similar inputs in the future. > > The module won't see its own history. It will rely on your advice balancing being concrete and being generalizable. > > In your advice: > - Avoid boilerplate. Offer advice that would change the module's behavior for the better in the future. > - Ensure that advice offered to a module M is specific to that M's specific sub-task, not the overall program. > - Rely on contrasting the behavior of the worse trajectory against the better trajectory in making recommendations. > - Ensure each unique module name appears exactly once as a key in the advice dictionary. Here's what an actual rule might look like: "When dealing with math word problems, always identify the numerical values first before attempting to set up equations. Focus on extracting 'what we know' versus 'what we need to find' as distinct steps." - `append_a_demo`: This is the second strategy that SIMBA can apply. It just adds a successful trace to the prompt as a few-shot example (rather boring in comparison :D) 7. These newly created candidates will be evaluated on the mini-batch again and the best one will be added to a list of “winning candidates” and all newly created candidates will be added to the global candidate pool. 8. After a defined number of rounds (controlled by `max_steps`), all “winning candidates” will be evaluated on the full training set and the best performing candidate will be returned by SIMBA. So that's how SIMBA works under the hood. Pretty clever, right? But when should you actually reach for SIMBA over something simpler like BootstrapFewShot or MIPROv2? Good question. In my internal experiments, SIMBA is more sample-efficient, higher performing and more stable compared to MIPROv2 (the other big DSPy optimizer, read the paper [here](https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11695)). But, since the algorithm uses the LLM itself to reason about its outputs, we need a reasonably strong underlying LLM. A 3b parameter model might perform worse with SIMBA compared to a simpler optimizer like `BootstrapFewShot` or `MIPROv2`, but - as always - you gotta test it. As you can see, SIMBA combines a lot of interesting ideas from genetic algorithms, the multi-armed bandit and self-reflection to create a very powerful way of teaching LLMs new tasks. It’s a kind of prompt-space based reinforcement learning and this whole area is super interesting: it’s approachable for a lot of people because it doesn’t need a huge number of GPUs, it’s much more data-efficient than supervised fine-tuning and much more “rollout-efficient” than weight-based reinforcement learning like GRPO (that’s the claim of the GEPA paper anyways). And it works with closed-source models or models behind an API as well. You don’t need access to the underlying weights. Okay, so that was SIMBA in a nutshell. It's a clever approach that shows how far prompt optimization has come - from simple few-shot examples to self-reflective algorithms that improve themselves. If you're working with complex DSPy programs, definitely give it a try. ### FootnotesYes, this is a description of how the dspy.SIMBA optimizer works.

— DSPy (@DSPyOSS) July 13, 2025

> a review/reflect stage along the lines of "what went well? what didn't go so well? what should I try next time?" etc. and the lessons from this stage feel explicit, like a new string to be added to the system… https://t.co/IN6D26BiGC pic.twitter.com/IIKxy5G7re

1. This is basically the point where the algorithm balances exploration vs. exploitation - should it pick the best performing candidate and try to improve it further (exploitation) or should it try and improve a worse performing candidate (exploration)? It would be interesting to explore other ways of sampling the candidates here. This step boils down to a multi-armed bandit problem, which has several other interesting algorithms, like “Thompson Sampling” or “Upper Confidence Bound”, which may or may not perform better than softmax sampling in this algorithm.